- Resources

- News

-

-

Get Email Updates

Sign up for STOP's emails and never miss an update on our latest work and the tobacco industry's activity.

-

Get Funding

Ready to tackle industry interference? You could be eligible for a grant.

-

Share a Tip

Do you have information on tobacco industry misconduct in your country? Let us know.

-

Get Email Updates

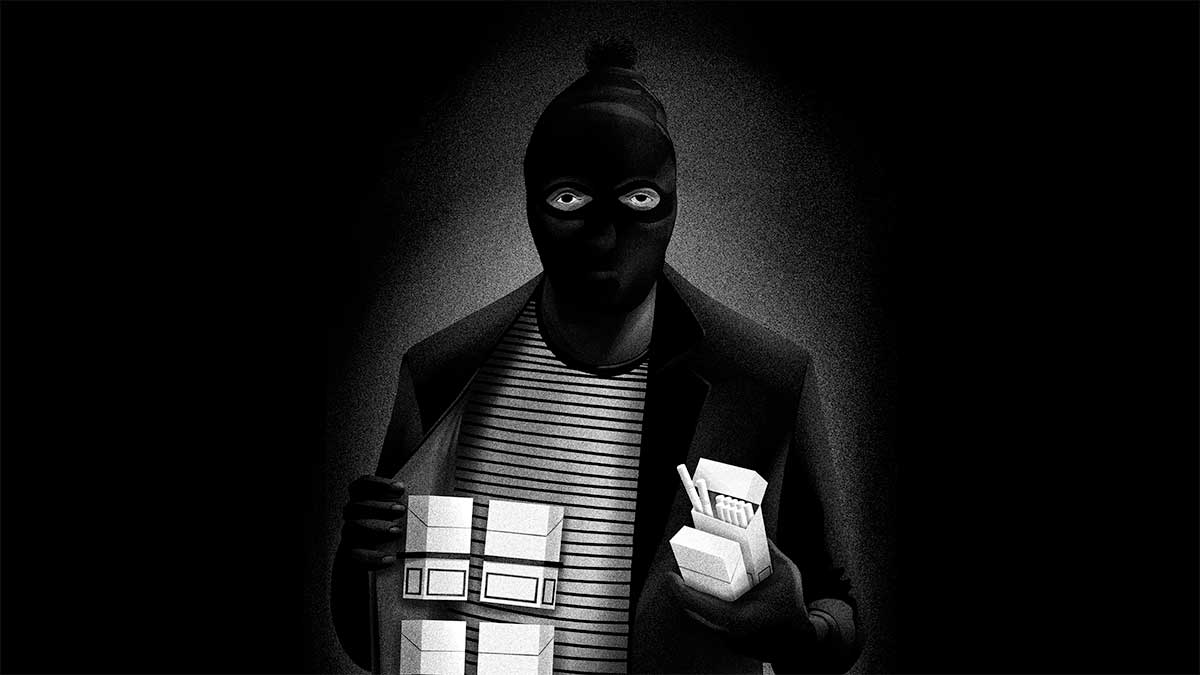

All over the world, tobacco products are being bought and sold on the black market. This is known as illicit tobacco trade, and it has real and serious consequences. But there are also those who stand to gain from it—just maybe not always who you’d suspect.

Intro to illicit tobacco trade

Around 98% of cigarettes on the black market were originally made by legitimate tobacco manufacturers. Unlike counterfeit cigarettes, which are labeled with fake logos and trademarks meant to look like genuine tobacco company products, most smuggled cigarettes are manufactured by real tobacco companies to be sold legally, but are then diverted at some point along their supply chain and end up on the black market.

Whether a cigarette is made, distributed or sold illegally (or all three), it creates a ripple effect of harm that starts with individuals and extends to entire economies and governments.

Illicit tobacco trade hurts…

People in your community. Black market tobacco products can be up to 50% cheaper than products sold legally. When cigarettes are cheap, they become more accessible to underage smokers and people of lower socioeconomic status. The affordability of illicit products makes it more likely these groups will start—and continue—smoking. Smuggled and counterfeit cigarettes are also able to skirt tobacco control measures proven to reduce tobacco use, like plain packaging, health warnings on packs and age restrictions on sales. The toll is substantial: A 2009 report estimated that if illicit trade were eliminated, around 164,000 lives would be saved annually around the world starting in 2030.

Your country’s economy. When tobacco products are sold on the black market, many of the taxes meant to be paid on them go unpaid. This tax evasion leads to significant losses in government revenues—up to $40.5 billion globally. This same 2009 report estimated that, were illicit trade to end, low- and middle-income country governments could gain more than $18 billion in tax revenue and high-income countries could gain up to $13 billion. These funds are needed now more than ever, as governments around the world struggle to sustain their economies during a pandemic that has led to job loss, over-burdened health care systems and the tragic, overwhelming loss of life.

Public safety and good governance. Put simply, illicit tobacco trade is illegal, and its existence indicates the presence of, and facilitates, corruption, organized crime, money laundering and terrorism. A 2010 study found that cigarette smuggling helped rebel groups in Africa fund their activities, and a 2012 report on illicit trade concluded that the money made off of illicit trade may fund other criminal activities—including terrorism.

Illicit tobacco trade helps…

The tobacco industry. While tobacco companies publicly condemn illicit trade, evidence suggests they have embraced it as a way to get and keep people addicted, enter new markets, partner with governments and agencies and fight against tobacco control measures.

When cigarettes are cheaper, as smuggled cigarettes often are, they’re more accessible. When more people start smoking—or don’t quit—the tobacco industry enjoys a strong customer base and secured future profits. Smuggled products that otherwise wouldn’t be in a given market can also create brand awareness and a demand for the product, softening tobacco companies’ entry into new markets. British American Tobacco was alleged to have used this method to help gain entry into the former Soviet Union market after its collapse in 1991.

Illicit trade also helps open the door for interaction with governments and agencies, and ultimately lets the industry paint itself as part of the solution. Despite the allegations surrounding the industry’s participation in illicit trade, it has boldly made donations to the European Antifraud Office, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime and Interpol. Tobacco companies try to insert themselves into regulatory processes by providing training for law enforcement agencies (Philip Morris International claims to have “trained” more than 6,000 officers across more than 20 European countries in 2019). If illicit trade ended, or was even drastically reduced, these opportunities to build influence with decision-makers could likely dissolve. By citing industry-funded data, which often presents inflated illicit trade estimates, tobacco companies can portray the problem as growing and perpetuate partnerships with these agencies.

The tobacco industry has adopted the proliferation of illicit trade as an argument against several proven tobacco control measures. It claims that plain packaging will lead to an increase in smuggling, though evidence from the U.K. and Australia shows it does not. Another common refrain from the industry is that illicit trade will grow if increased taxes make cigarettes unaffordable, even though countries with higher tobacco taxes and prices tend to have smaller illicit cigarette markets.

Illicit tobacco trade can be stopped

The Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products, to which there are currently 62 Parties, lays the groundwork for putting an end to tobacco on the black market. A key goal of the Protocol is to secure the tobacco product supply chain so that products can’t slip undetected onto the black market. A crucial measure that can help achieve this is the implementation of tracking and tracing systems that are independent from the tobacco industry.

With a multisectoral approach, international cooperation and a commitment to keeping the tobacco industry from interfering with these efforts, we can end the harm illicit tobacco trade inflicts on people, economies and societies.