- Resources

- News

-

-

Get Email Updates

Sign up for STOP's emails and never miss an update on our latest work and the tobacco industry's activity.

-

Get Funding

Ready to tackle industry interference? You could be eligible for a grant.

-

Share a Tip

Do you have information on tobacco industry misconduct in your country? Let us know.

-

Get Email Updates

For decades, Big Tobacco publicly denied what it internally knew to be true. It ran deceptive campaigns, misled policymakers even when under oath and paid for biased research to help create confusion. The longer the truth was withheld, the more people smoked unaware of the damage it was causing to their bodies. Regulations were delayed that may have given people the information they needed and protected them from industry predation.

Today, the industry continues making potentially dangerous claims about the safety and “reduced-risk” nature of its newer products, such as heated tobacco products. But can we really take what cigarette corporations say at face value? The industry’s track record of deception and putting profit before health suggests we cannot.

Here’s a decade-by-decade look at some key tobacco industry lies that remind us that what the industry knows and what it says aren’t always the same thing.

1953: “There is no proof that cigarette smoking is one of the causes [of lung cancer.]”

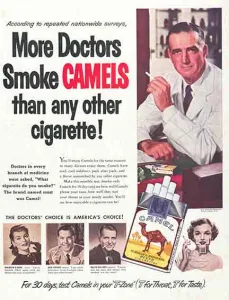

In the 1950s, extensive studies from the United Kingdom and the United States pointed to smoking as a likely cause of lung cancer. While it wasn’t the first time the correlation was explored, the public began to worry.

Even researchers working for the tobacco industry appeared interested in the link. In a 1953 confidential report for RJ Reynolds, one researcher noted that clinical data supported the theory that cigarettes could be cancer-causing.

The tobacco industry had to respond to reassure existing and potential customers. In 1954, tobacco companies in the U.S. released the “Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers.” In the piece, the tobacco companies denied the link to cancer, stating: “We believe the products we make are not injurious to health.” They sought to cast doubt on the independent studies’ findings related to lung cancer, saying “There is no proof that cigarette smoking is one of the causes.” Research suggests, however, that tobacco companies knew by the mid-1950s that their products were linked to cancer and were addictive.

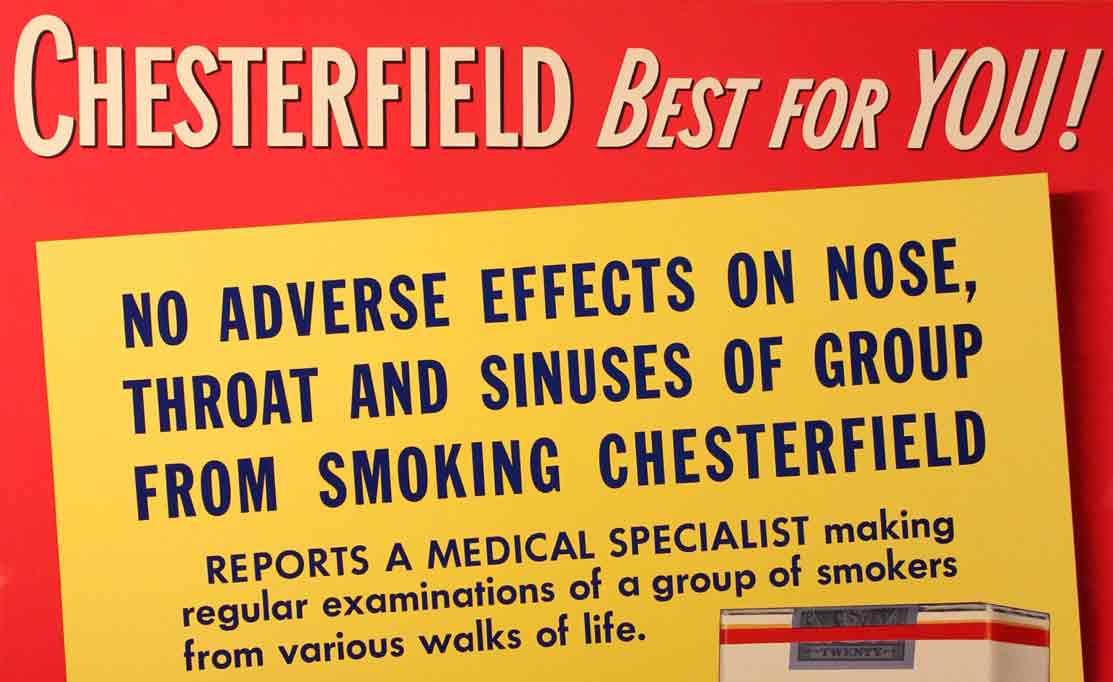

1964: “We don’t accept the idea that there are harmful agents in tobacco.”

In the early 1960s, two reports came out that clearly stated that smoking was a proven cause of lung cancer. The 1962 report from the Royal College of Physicians and the 1964 report from the U.S. Surgeon General publicly concluded that cigarette smoking is a cause of lung cancer, and that smoking “far outweighs” other risk factors.

Yet the industry continued to publicly deny the harm of cigarettes. Philip Morris’s stance in 1964 was: “We don’t accept the idea that there are harmful agents in tobacco.”

To try to dissuade people from cutting back or quitting, the industry turned to a tactic it had used in the past and still uses today: creating doubt and confusion around public health research. An internal 1969 memo from a British American Tobacco (BAT) subsidiary said it in plain language: “Doubt is our product since it is the best way of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the mind of the public. It is also the means of establishing a controversy.”

CEOs of seven major tobacco companies testified under oath to the U.S. Congress that they did not believe nicotine to be addictive.

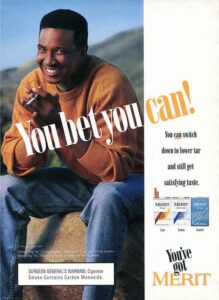

1976: “Twelve year effort ends with unprecedented flavor in low tar smoke.”

While continuing to publicly deny the health harms of smoking, the industry simultaneously began promoting “light” and “mild” cigarettes. These products, in addition to the filtered cigarettes the industry had introduced in the ‘50s, gave the perception of being safer and were marketed with “implied promises of reduced risk to health.” This 1976 Philip Morris ad, for example, boasted the headline, “Twelve year effort ends with unprecedented flavor in low tar smoke.” The ad promoted the cigarette’s “enriched flavor” while claiming it delivered “the lowest tar levels in smoking today.”

A BAT document from 1977 revealed the industry’s motivations: “All work in this area should be directed towards providing consumer reassurance about cigarettes and the smoking habit. This can be provided in different ways, e.g. by claimed low deliveries… and by the perception of ‘mildness.’”

Evidence suggests that cigarette companies knew that these modified products did not actually offer any health benefits. It turned out that smokers often took deeper and more frequent puffs. A scientist for BAT said in 1979 that, “the effect of switching to a low-tar cigarette may be to increase, not decrease, the risks of smoking.”

1987: “I know there’s no proof my smoke can hurt you.”

In the 1980s, a new threat to the tobacco industry surfaced: the public’s growing concern over the dangers of secondhand smoke. These fears were confirmed when the U.S. Surgeon General released a report in 1986 concluding that secondhand smoke caused disease.

A year later, Philip Morris publicly refuted the notion that secondhand smoke was harmful, releasing an ad that read, “I know there’s no proof my smoke can hurt you.”

To try to prevent smokers from having another reason to cut back or quit, and to persuade policymakers there was no need to implement smoking bans in public places, the industry sought to counter the research. In 1988, Lorillard, Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds set up the Center for Indoor Air Research. The Center, which was shut down in 1998, was eventually declared by the United States Department of Justice to have been set up to “fraudulently mislead the American Public” about the effects of secondhand smoke.

1994: “I don’t believe that nicotine or our products are addictive.”

In 1994, CEOs of seven major tobacco companies testified under oath to the U.S. Congress that they did not believe nicotine to be addictive. Joseph Taddeo, then-President of U.S. Tobacco Company, told Congress: “I don’t believe that nicotine or our products are addictive.” The other six CEOs agreed.

Yet, the tobacco industry’s knowledge of the addictive nature of nicotine goes back to at least the 1960s. Tobacco companies’ statements were clear. An executive from Brown and Williamson, a BAT subsidiary, wrote in 1963: “Nicotine is addictive. We are, then, in the business of selling nicotine, an addictive drug.” A BAT document from 1967 stated: “Smoking is an addictive habit attributable to nicotine and the form of nicotine affects the rate of absorption by the smoker.”

Sifting through modern tobacco industry lies

Tobacco industry cover-ups and deception didn’t end in the 20th century. Since then, the industry has claimed to care about the environment, yet is a major contributor to carbon emissions, water contamination, litter and other environmental harms. It has claimed to be working to stop child labor in tobacco, but continues to perpetuate its root causes.

Cigarette corporations are even updating their narratives with new slogans: Philip Morris International is promoting a “smoke-free future” and BAT is promising “A Better Tomorrow.”

But the public and policymakers must not forget how the tobacco industry knowingly denied the cancer link, misleadingly promoted new products as having health benefits, contested the harms of secondhand smoke, set up an organization to produce research that aligned with its interests and purported that nicotine was not addictive, despite knowing otherwise. Decades of duplicitous behavior and lies serve as proof that tobacco corporations act in the interest of their profits, not public health.