- Resources

- News

-

-

Get Email Updates

Sign up for STOP's emails and never miss an update on our latest work and the tobacco industry's activity.

-

Share a Tip

Do you have information on tobacco industry misconduct in your country? Let us know.

-

Get Funding

Ready to tackle industry interference? You could be eligible for a grant.

-

Get Email Updates

Sabotaging Policy

November 23, 2020

Here’s the bad news.

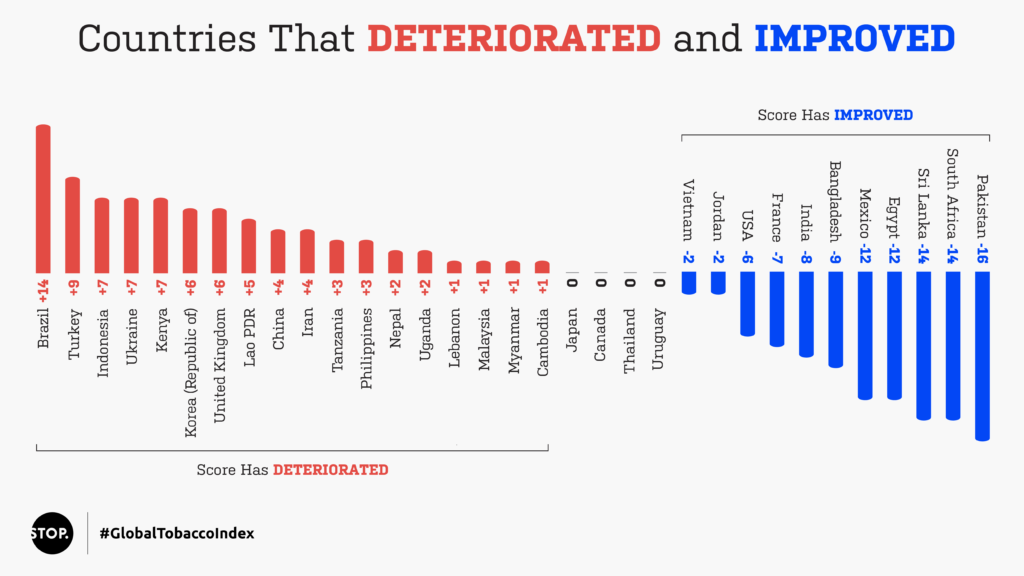

The tobacco industry is relentless in its pursuit to addict new users to its products. The recently released Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2020 (the Global Tobacco Index) illustrates the industry’s multi-faceted approach to ensuring its products are available to as many people as possible. Whether tobacco companies are lobbying for the acceptance of their addictive new products, trying to delay or reverse tobacco control legislation or meddling in countries’ tobacco tax laws, the Global Tobacco Index indicates that the industry shows no sign of truly changing.

The new Global Tobacco Index, which uses civil society reports to evaluate 57 governments’ responses to industry interference, also shows cases where governments need to step up their fight against industry interference and defend the policies and people they’re obligated to protect. For instance, the Ministry of Finance in Colombia succumbed to industry pressure that resulted in no tax increases on tobacco products. In Nigeria and Vietnam, the government allowed the tobacco industry to sit on the regulatory committees that determine the standards for tobacco products. The government of Ghana has yet to implement a 2018 ban on e-cigarettes and shisha, and in Argentina, senior ministers mingled with members of the tobacco industry at an event hosted by an organization financed by Philip Morris International (PMI).

Here’s the good news.

The Global Tobacco Index also indicates that many countries are successfully fighting back. Governments are rejecting partnerships with tobacco companies, banning tobacco products to protect the public’s health during the pandemic and making sure tobacco companies don’t get a say in public health policy. Here are several cases where governments prevailed.

Pakistan didn’t give in to the industry’s tax policy pressure.

The Ministry of Health worked with civil society organizations to help revert the country’s three-tier tax system back to a two-tier system, closing a loophole that placed the most-sold tobacco brands in the lowest tier of taxes, where less tax had to be paid.

Why it matters: Giving tobacco companies and their products preferential tax treatment can make tobacco products more accessible to consumers and can cause governments to miss out on much-needed tax revenues.

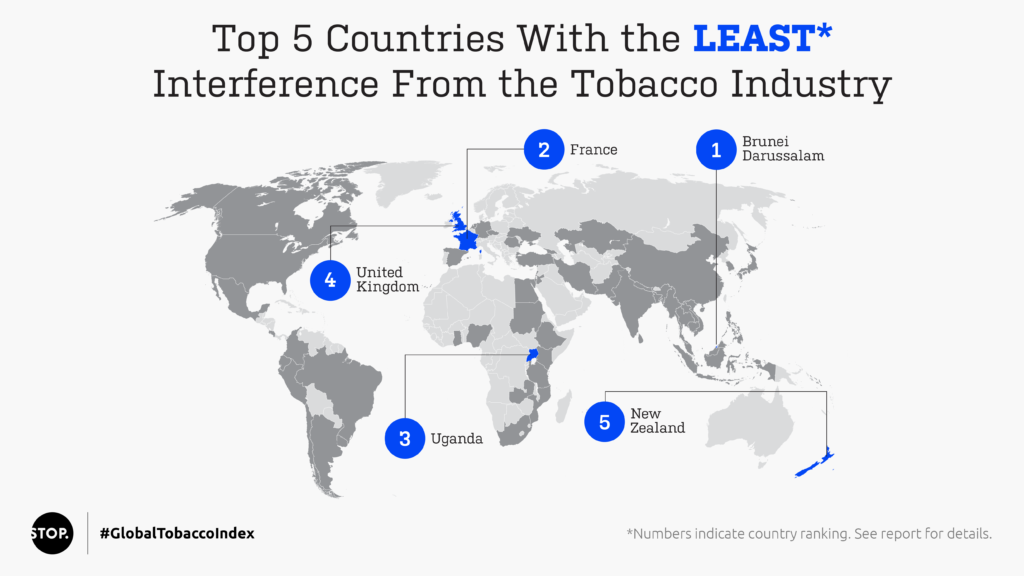

The Netherlands blocked industry interference in policy development.

The country’s tobacco control policy document specifically calls for the exclusion of the tobacco industry when developing public health policies about reducing tobacco use.

Why it matters: The tobacco industry’s interests are in direct and irreconcilable conflict with the interests of public health. When the industry has a seat at the policymaking table, it will likely advocate for its own commercial interests, ultimately to the detriment of public health.

Peru publicly disclosed an important meeting.

In a move to support transparency, the government publicly disclosed a meeting it had with the tobacco industry where PMI proposed acceptance of its heated tobacco product, IQOS, into the Peruvian market.

Why it matters: When meetings between government bodies and the tobacco industry happen behind closed doors, other departments, civil society groups and the general public don’t have the chance to recognize and push back on industry interference.

Sri Lanka powered through with plain packaging.

Even after facing court challenges for applying pictorial health warnings on cigarette packages, the government approved plain packaging for tobacco products.

Why it matters: Plain packaging strips tobacco products of their marketing allure and has been shown to increase the salience of health warnings and boost negative feelings about smoking.

Brunei Darussalam prevented interference before it started.

The Prime Minister’s office issued an official code of conduct, applicable to all civil servants, to prohibit unnecessary interactions with the tobacco industry and require that any interaction that is required (for regulation) is transparent. The code also calls for the rejection of partnerships with and sponsorship from the tobacco industry.

Why it matters: Without a code of conduct that lays out the rules for interacting with the tobacco industry, civil servants—particularly those working in non-health departments—may not be aware of the damage that can occur when they interact with the industry. Having official guidelines helps protect them from the industry’s persuasive tactics.

Several countries enacted pandemic protections for public health.

All over the world, governments sprang into action to protect their populations from the effects of COVID-19. Mexico prohibited the sale of e-cigarettes; the USA categorized vape, smoke and cigar shops as non-essential, forcing them to temporarily close; three municipalities in the Philippines banned the sale of cigarettes; and the governments of India and South Africa banned the sale of tobacco products.

And here’s the best news.

Other countries can do many of these things, too. Implementing Article 5.3 of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), a global treaty to reduce tobacco use, gives governments the tools and ability to protect its policies from the tobacco industry.

Check out the full Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2020 to learn more about how countries are successfully standing up to the tobacco industry’s commercial interests—and find out where there’s still work to do.

About the report: The Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index (Global Tobacco Index) is a global survey of how governments are responding to tobacco industry interference and protecting their public health policies from commercial and vested interests as required under the FCTC.

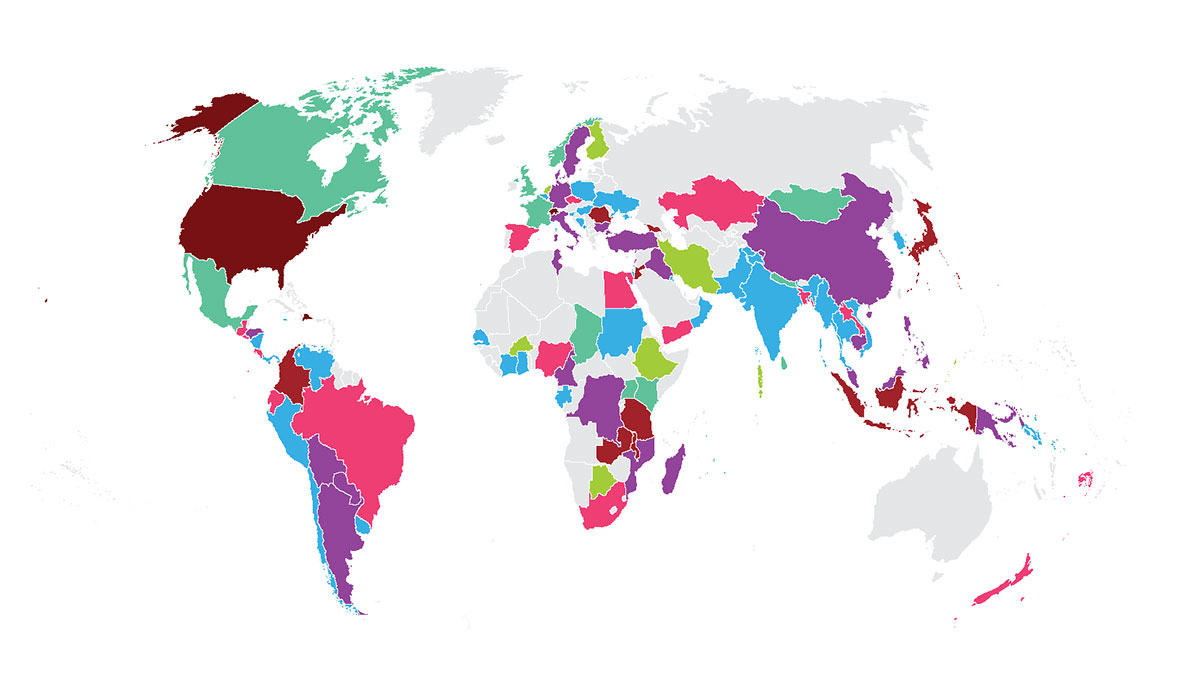

For this year’s Global Tobacco Index, the Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control (GGTC), a STOP partner, utilized civil society reports from participating nations to rank 57 countries that cover about 80% of the world’s population.