- Resources

- News

-

-

Get Email Updates

Sign up for STOP's emails and never miss an update on our latest work and the tobacco industry's activity.

-

Get Funding

Ready to tackle industry interference? You could be eligible for a grant.

-

Share a Tip

Do you have information on tobacco industry misconduct in your country? Let us know.

-

Get Email Updates

Sabotaging Policy

March 13, 2025

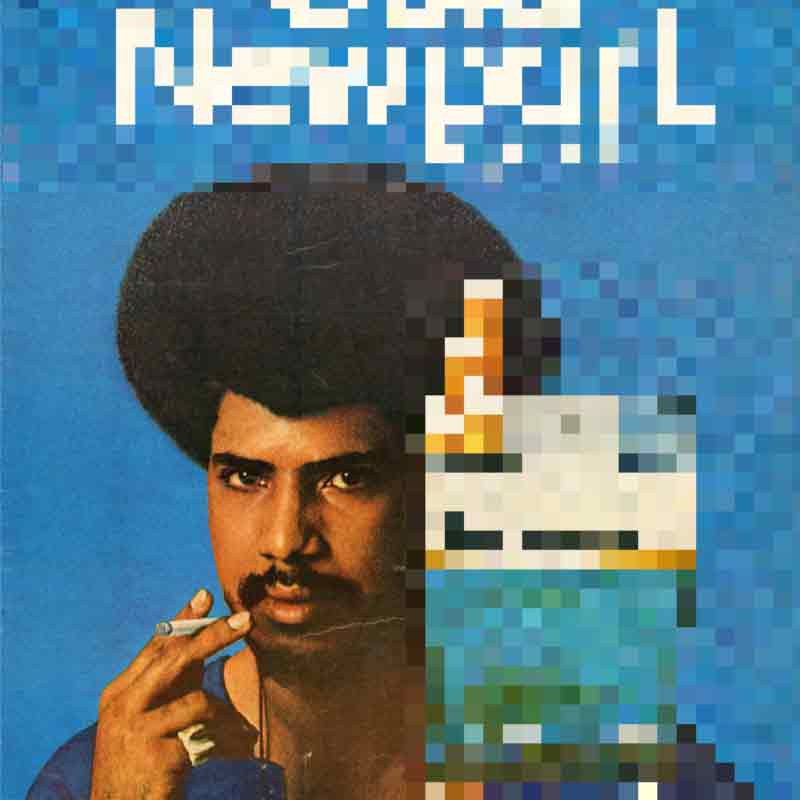

Watch an American TV show. If a Black character is smoking, chances are they’re pulling menthol cigarettes from a green box.

“On the show ‘The Wire,’ they should have given Newports a costarring role because Newports was in every episode,” says Carol McGruder, Co-Chair of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council (AATCLC).

Media portrayals of Black people smoking menthol cigarettes reflect a harsh reality: In the United States, about 80% of Black smokers smoke menthols, compared to about 43% of adult smokers overall. Menthol cigarettes are known for being easier to start and harder to quit, contributing to disproportionate tobacco-related illness and death among Black Americans.

Every year, tobacco use kills 45,000 Black people in the U.S. “When those people die, it destabilizes our families, it destabilizes our communities, and it causes irreparable, intergenerational harm,” says McGruder.

This disproportionate use of menthol tobacco in the Black community isn’t by chance. It’s the result of “relentless, pernicious, racist targeting,” says McGruder, and it’s what she and her colleagues are working to stop. With the recent withdrawal of the proposed menthol ban in the U.S., this work is more important than ever.

The industry has been pushing menthol on Black people for decades

In STOP’s video series, “Lives at Stake: True Stories of People Challenging Big Tobacco,” McGruder shares that she has been an activist her whole life, but that her fight against the tobacco industry began in the 1990s. By that point, the industry had been heavily targeting its menthol marketing to Black communities for at least four decades and had hooked countless Black smokers.

In the 1960s, the tobacco industry began ramping up its advertising assault on Black people. Tobacco companies plastered menthol billboards in predominantly Black neighborhoods and aggressively advertised in Black-run magazines such as Ebony and Jet.

In the 1970s, R.J. Reynolds commissioned a study on how to advertise on buses with predominantly Black ridership that passed through white neighborhoods. (Their abhorrent solution: Put ads that exclusively featured Black models and culture on the interior of the bus only.) In the 1970s and ‘80s, they sent vans into cities throughout the country and distributed free menthol cigarettes. Their intentions were clear: An industry marketing document laid out how the Kool brand intended to distribute almost 2 million free cigarettes to “housing projects, clubs, community organizations and events where Kool’s black young adult target congregate.”

While many forms of tobacco advertising are banned in the U.S. today, tobacco companies still find ways to target the Black community. In 2020, following the police killing of George Floyd, tobacco companies that make products that are disproportionately used by Black consumers co-opted “Black Lives Matter” messaging on social media to promote their brands. A 2021 study also showed that price promotions for menthol tobacco are more common in Black neighborhoods, where menthol cigarettes are cheaper and advertised more heavily.

“To think that they sit in a room like this and they divide us up and they strategize about how they’re going to keep… their hooks in us, that’s something that fuels me,” says McGruder.

45,000 Black Americans die every year from tobacco use

Solutions have come from within the Black community—and the industry has noticed

McGruder is in good company in trying to end this racist marketing. Multiple Black-led organizations have publicly called for menthol cigarettes to be banned: McGruder mentions Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., a historically Black sorority; the National Medical Association, the largest organization representing Black physicians and health professionals; and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. While menthol is currently banned in some U.S. cities and states, including in California where the AATCLC is based, the FDA’s 2021 proposed ban on menthol was put on hold in 2024 and “withdrawn” in 2025.

A menthol ban could save an estimated 255,000 Black Americans within 40 years. It would also significantly hurt industry profits. That’s why Reynolds American, maker of Newport cigarettes, apparently covertly funded public campaigns that opposed the ban and likely contributed to the decision to withdraw it.

Reporters have uncovered evidence that suggests Reynolds also funded a group whose ads made the unsupported claim that banning menthol tobacco would “enrich cartels and terror groups.” The tobacco company also hired Black lobbyists and sponsored the National Action Network, led by Rev. Al Sharpton, to flip the script and convey that a menthol ban would hurt Black Americans. They say, “…if we take [menthol] off the market, that that’s racist because that’s quote-unquote ‘what Black people like,’” McGruder explains.

She urges Black organizations to reject tobacco money and influence. “When a Black organization steps back and stops taking the money, cuts off that relationship, the industry is like a lonely lover waiting for that call at midnight to woo you back.” She commends the leaders who do not take tobacco money. She says, “There’s no upside to dealing with the industry. There’s no upside to the killing of 45,000 Black people [per year].”

To tackle the work ahead, celebrate the wins and know that change will come

Whether advocates are working to protect people who face discrimination, youth, the environment or public policies from the tobacco industry’s harms, they know that change won’t come all at once. McGruder’s advice? Pace yourself. Celebrate the wins, but know that what you’re doing is “not going to make change tomorrow or maybe in five years. But we know that change is coming and that we have to hold fast and we have to keep doing the right thing,” she says.

Another piece of advice for tobacco control advocates: Support one another. Find people who are like-minded, among whom there is mutual respect and trust, and the work will be easier. “This is a sad subject,” she says, “so we need to have joy in our lives.”

McGruder is focusing now on what she calls the endgame. Instead of trying to chase an industry that will always evolve and create new products, it’s time to get ahead of them. “The only way to get ahead of [the tobacco industry] is to think about dismantling this whole machine,” she says.

For the sake of future generations, that is a goal worth working towards, however long it takes and however difficult the path.