- Resources

- News

-

-

Get Email Updates

Sign up for STOP's emails and never miss an update on our latest work and the tobacco industry's activity.

-

Get Funding

Ready to tackle industry interference? You could be eligible for a grant.

-

Share a Tip

Do you have information on tobacco industry misconduct in your country? Let us know.

-

Get Email Updates

By Prof. Anna B. Gilmore & Dr. J. Robert Branston

As Philip Morris International (PMI) shareholders meet online this week, the world’s health is in a precarious position, but so too is PMI. Already dealing with a long-term decline in its core business as people turn away from smoking, it now faces two new external crises (COVID-19 and the associated major economic recession) and a failure to diversify its tobacco-related products compared with other tobacco companies, which should concern investors.

COVID-19 compounds existing trends

Highly addictive products, no matter how deadly, tend to be insulated from external shocks. It is no surprise therefore that, so far, tobacco stocks are faring well in the current crisis, with all four transnational tobacco companies (TTC) showing significant increases in their share prices over the last month.

But COVID-19 may yet prove difficult for tobacco companies. Evidence indicates that smokers are at greater risk of both severe illness and death from the coronavirus, and the World Health Organization and governments worldwide are calling on smokers to quit. With evidence showing that smokers tend to quit or reduce consumption in response to health shocks, and with this health shock being universal, global cigarette sales could ultimately fall as a result of coronavirus.

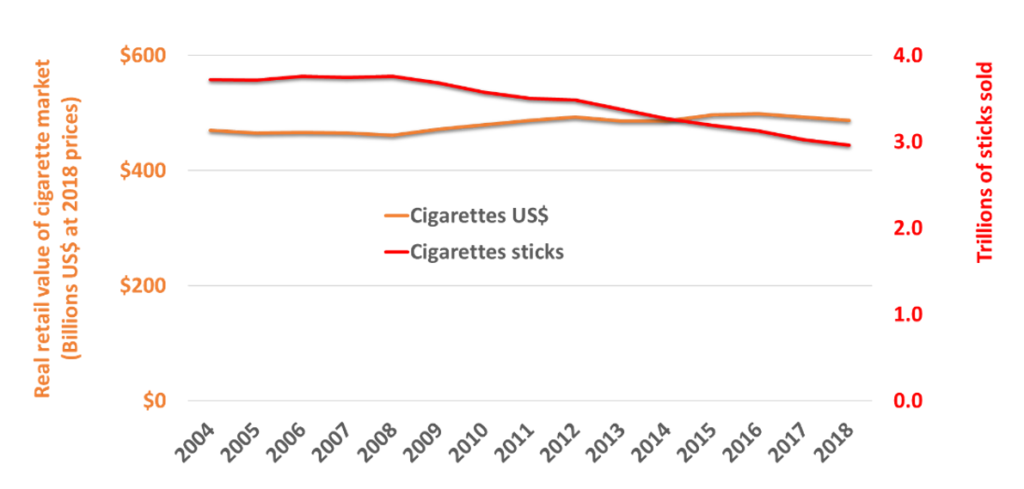

This danger comes at an inopportune time for cigarette manufacturers. Global cigarette sales (data exclude China) have already seen a declining trend, with falls of around 20% over the last decade, with the greatest declines in the more profitable markets. While the industry was initially able to increase cigarette prices sufficiently to offset declines in profitability, this is no longer the case and since 2016 the profitability of cigarettes, as measured by their real retail value, has also been declining. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Trends in volumes and value of global cigarette sales (202 markets excluding China)

Source: Euromonitor, downloaded December 2019, our figure

These underlying trends, likely to continue given the growth in tobacco control legislation and the additional impact of COVID-19, will be further compounded by the inevitable economic recession. While tobacco may historically have been relatively recession-proof, there is ample evidence that recession can lead to smoking rate declines in many groups. It may also further encourage the existing trend for more price-conscious smokers to down-trade to cheaper, and hence less profitable, products thereby further exacerbating the declining profit trend. With PMI’s cigarette portfolio heavily skewed to the premium end of the market and including limited roll-your-own options, PMI may be particularly vulnerable to down-trading pressures.

Not only is the lockdown recession predicted to be the worst since the Great Depression, it is the first piggy-backed on an acute global health crisis in which smoking and smoking-related harm are a factor, and where a wide variety of products is available to replace the cigarette. To put things in perspective, in the 2009 financial crisis, not only was the global GDP decline just -0.1% compared with the -3% predicted now, but e-cigarettes had only just started to emerge on the market. Today, numerous other alternatives to the cigarette are available (see below). All this suggests the recessionary impacts on tobacco may be greater than expected and perhaps particularly for PMI.

PMI’s particularly bad position: the least diversified and highest-risk product portfolio

Despite PMI’s claimed commitment to harm reduction, it is arguably the least diversified TTC with the highest-risk product portfolio. It has two major products—the cigarette and IQOS, its flagship heated tobacco product (HTP)—which respectively account for 92% and 8% of volumes (and 81% and 19% of net revenue).

PMI has invested heavily in developing IQOS and now uses the HTP to claim it wants to move its entire business away from combustion tobacco in the name of health. Unfortunately for PMI there is no independent evidence that IQOS is any safer than cigarettes. While HTPs may reduce emissions of, and exposure to, harmful compounds, there is no independent evidence that this translates to reduced harm.

Indeed, independent analyses of PMI’s own data suggest IQOS may be as harmful as smoking. One of these studies found the lung and immunosuppressive effects of switching to IQOS (which are clearly critical in the current health crisis) were indistinguishable from continuing conventional cigarettes. It also flagged major concerns about PMI’s data and misleading conclusions. These build on similar concerns raised by several former PMI scientists. Furthermore, PMI claims that IQOS is “smoke-free,” and frames its publicity around this idea, but this is also contested.

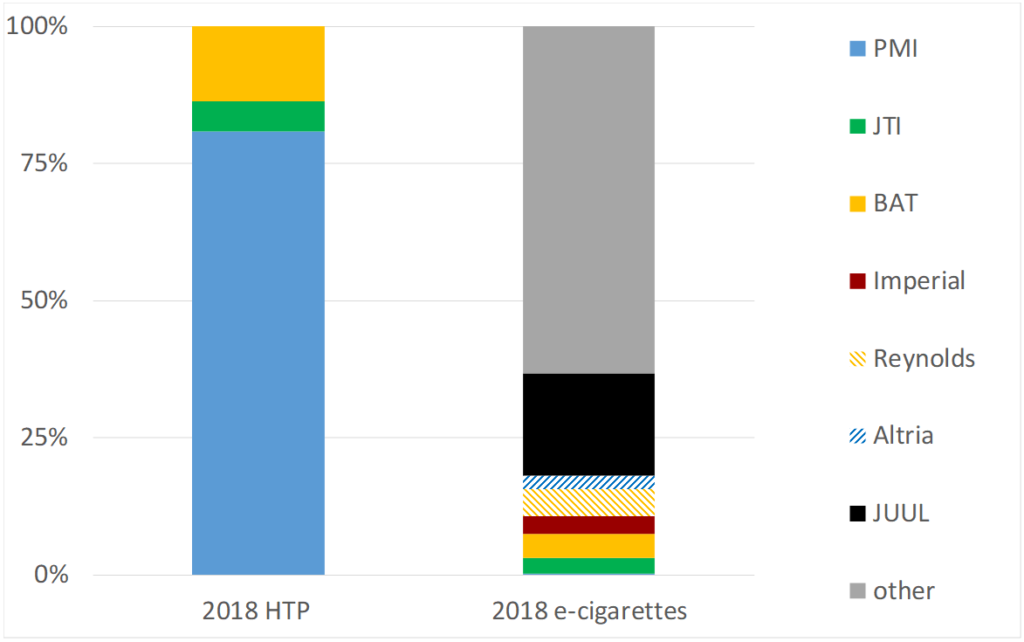

Having previously had only very minor e-cigarette interests, PMI recently launched an e-cigarette under its IQOS brand and its share of the global e-cigarette market remains a paltry 0.3%. The other TTCs have significantly greater shares (albeit still small) of the global e-cigarette market (Figure 2) and all bar PMI also now sell new oral tobacco and/or nicotine products. Although the exact risks of these “next generation” tobacco and nicotine products are not yet known, when considering risks in individual users compared with cigarettes, the new oral nicotine and snus-like tobacco products (as opposed to traditional high-risk oral tobaccos) will be at the lower end of the risk profile. E-cigarettes are also significantly less harmful than cigarettes, while HTPs, like IQOS, will be at the higher end of the risk profile, closer to cigarettes which kill two in three long-term users.

This has two implications. First, given the array of other less risky consumer alternatives available (in additional to pharmaceutical nicotine), there is little role for HTPs. Second, the mismatch between PMI’s science and its claims to “normalize” IQOS may again expose PMI to risk of litigation.

The better news for PMI shareholders is that, based on operating profits and ignoring the sunk investment costs, HTPs are currently even more profitable than cigarettes. However, as this relies on their preferential tax status (relative to cigarettes) in many jurisdictions, in turn dependent on claims that HTPs are lower risk, this benefit may be short-lived.

Figure 2: Global HTP and e-cigarette market share 2018 by company

Source: Euromonitor downloaded Nov & Dec 2019, our figure

Paying for the crisis: bad publicity and declining influence create a perfect storm

More broadly, COVID-19 will bring the appalling health and economic impacts of smoking into even sharper focus than usual and once the reckoning starts, tobacco companies will be squarely in the firing line. Three inter-related impacts are likely.

First, once the crisis passes, governments will be re-energized to implement and enforce tobacco control policies realizing that, if their health systems were not already struggling to cope with the entirely preventable burden of tobacco-related diseases, the health and economic impacts of COVID-19 would not have been so appalling. It is also likely that in many countries the death toll from COVID-19 will be less than the annual deaths from tobacco, thus further highlighting the need to address this problem.

Second, as governments look to fund their nations’ recoveries while meeting ongoing health systems costs, taxing tobacco products will be attractive as such taxes are among the most effective and publicly acceptable options. The World Bank has shown the “staggering poverty and economic burden” of tobacco and made the overwhelming case for increasing tobacco taxes in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to save millions of lives, reduce poverty and increase domestic resources for development. It estimates that raising cigarette excise tax rates in all developing countries by the equivalent of USD $0.25 per pack would generate an extra USD $41 billion in government revenue for LMICs. As evidence of the health harms of IQOS and HTPs is clarified, HTPs are likely to be taxed similarly to cigarettes, further denting PMI’s profits. Interest in “polluter pays” taxes—developed from the principle that those who produce the damage should bear the costs of managing it—are also gaining popularity in some countries and may gain particular traction once the link between smoking, smoking-related harms and the damage from COVID-19 is more clearly assessed.

Third, tobacco companies are likely to find their ability to prevent these tax increases and other policies that run counter to their interests increasingly stymied. They have long understood that their ability to secure policy influence depends on their credibility; hence their heavy investment in so called “corporate social responsibility” initiatives. Leaked PMI documents identify a company acutely aware of its pariah status and the need to overcome this simply in order to operate. Yet its attempts to do so via claims to “unsmoke” the world have been ridiculed amid evidence that it continues to buy up cigarette companies, launch new cigarette brands, market cigarettes to youth and challenge effective tobacco control legislation. Not only will the current crisis make it harder than ever for tobacco companies to launder their image, but PMI’s cynical attempts to distract from its products’ harms, for example through the donation of ventilators, will be identified as a sham—this is not genuine philanthropy but the image laundering that PMI has to engage in just to continue operating.

Conclusion

PMI shareholders have long been attracted to such a tobacco stock because of its ability to generate returns from the high profitability of tobacco. Going forward, they would do well to reflect on its prospects given that the value of tobacco sales is now falling, the number of less-risky alternatives is increasing and PMI is not as diversified as its competitors. Selling two major products, both of which cause major health damage, particularly respiratory damage, does not bode well given the current global health and economic crises. While IQOS may be selling well now, once users are aware of the evidence, that pattern should change and if PMI’s science is found to be inadequate, it could face litigation. While tobacco has traditionally been recession-resistant relative to other products, times are certainly changing, and PMI may be particularly exposed.

Notes:

For an overview of PMI’s next generation product strategy, see Next Generation Products: Philip Morris International. For more detail on IQOS Mesh and earlier products acquired by PMI, see E-cigarettes: Philip Morris International. Background information on HTPS, and more detail on IQOS and the HTPs of PMI’s competitors, can be found at Heated Tobacco Products.

To read more about PMI, see Addiction at Any Cost: Philip Morris International Uncovered.

Disclosure:

Dr. J. Robert Branston owns 10 shares in Imperial Brands for research purposes. The shares were a gift from a public health campaigner and are not held for financial gain or benefit. All dividends received are donated to tobacco/health related charities, and proceeds from any future share sale or takeover will be similarly donated.