- Resources

- News

-

-

Get Email Updates

Sign up for STOP's emails and never miss an update on our latest work and the tobacco industry's activity.

-

Get Funding

Ready to tackle industry interference? You could be eligible for a grant.

-

Share a Tip

Do you have information on tobacco industry misconduct in your country? Let us know.

-

Get Email Updates

Of the 8.7 million people who die every year from tobacco use, 1.3 million of them don’t even use tobacco. They’re the victims of secondhand smoke.

Secondhand smoke is more insidious than most people might think. The World Health Organization reports that any level of exposure to secondhand smoke is detrimental to health. In the short-term, exposure can cause headaches; dizziness; nausea; eye, ear and throat irritation; and respiratory distress. In the long-term, it can lead to heart disease and numerous cancers, with at least 69 compounds in secondhand smoke known to be carcinogenic. Exposure to tobacco smoke also increases an infant’s risk of sudden infant death syndrome.

The 2023 WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic emphasizes smoking bans in public places as a clear solution to protect non-smokers, particularly children. The report states that 74 countries have implemented national smoke-free laws. That may seem like a lot, but it only covers about one-quarter of the world’s population.* There’s a lot of work still to be done, and the tobacco industry stands in the way.

As early as the 1980s, the industry financed or created hospitality groups that publicly opposed smoke-free policies.

The tobacco industry stalls smoke-free policies that would save lives

The tobacco industry often tries to suppress policies that would reduce tobacco use and therefore threaten its profits. Since smoke-free policies—or, bans on smoking in public places like restaurants, bars, parks, public buildings and workplaces—help to reduce tobacco use, the tobacco industry tries to prevent or delay their implementation.

A common argument the industry uses is that smoking bans will harm businesses and the economy. The industry often targets this message at hospitality and tourism sectors, warning that smoking bans will drive patrons away from restaurants, bars, cafes and hotels, hurting hospitality employment and revenues.

The tobacco industry is known for using allies to further its agenda, and this narrative is no exception. As early as the 1980s, the industry financed or created hospitality groups that publicly opposed smoke-free policies. One of these was the Beverly Hills Restaurant Association, a front group in the United States created by a public relations firm on behalf of the tobacco industry, that was used to oppose California’s first 100% smoke-free restaurant ordinance in 1987.

Evidence shows hospitality groups have also been active in trying to suppress smoke-free policies in Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico and Slovenia. In addition, the industry and its allies have promoted “accommodation” programs—public relations campaigns to promote separate smoking and non-smoking sections in public places instead of completely smoke-free spaces—in Serbia, Kenya and Guatemala.

The truth behind the industry’s misleading arguments

Independent research, including a review of 97 studies across eight countries, has shown that smoke-free policies do not, in fact, harm businesses. Smoking bans actually have an overall neutral effect, neither significantly helping nor hurting sales and employment at restaurants and cafes. The WHO report cites several examples: A study of comprehensive smoke-free legislation in Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago showed that the arrival of tourists, the length of their stay and their tourism expenditure did not change after smoke-free legislation was introduced. Other studies have shown that smoke-free policies did not have negative impacts on the hospitality industry in Cyprus and Ireland. The same was found in Mississippi, Hawai’i and other states across the United States.

Allowing smoking, on the other hand, can cost businesses money. Companies may have to pay for increased cleaning and maintenance costs and higher health and hazard insurance premiums. Further, illness caused by tobacco use can lead to lower productivity and absenteeism among employees.

The economic benefits of smoke-free policies extend beyond bars and restaurants. The World Bank estimated that smoking restrictions can reduce overall tobacco consumption by 4 – 10%. Smoking bans reduce tobacco use by denormalizing smoking, making smoking less accessible and removing triggers to smoke for people trying to quit.

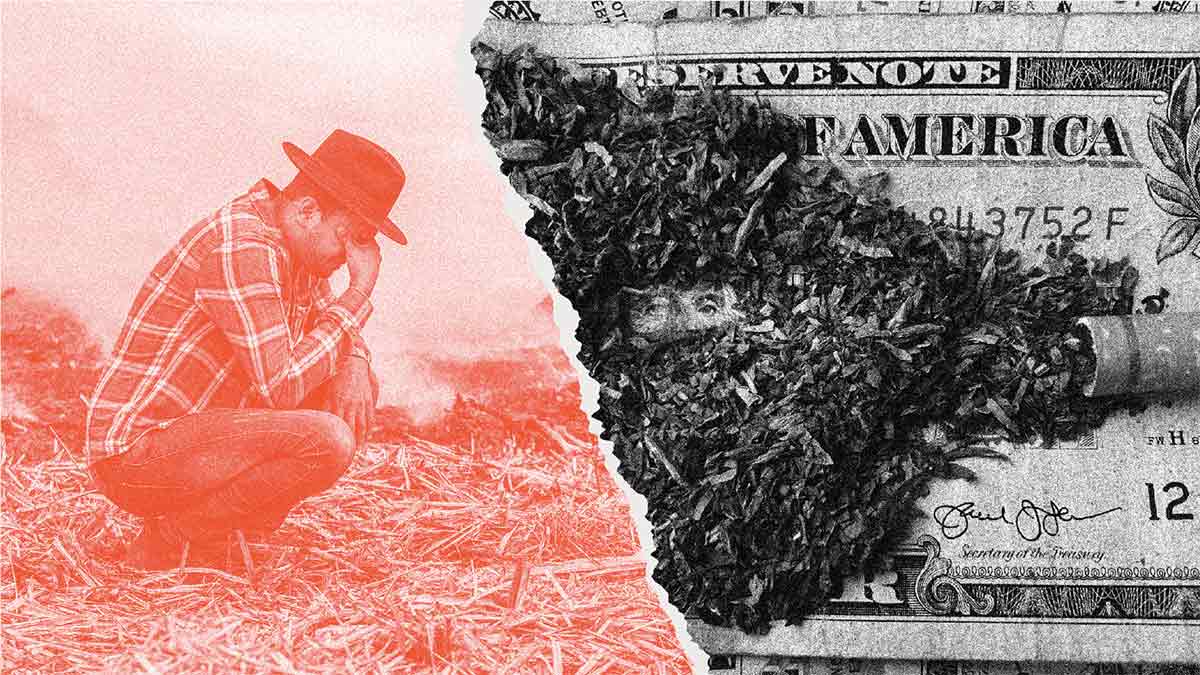

It also reduces non-smokers’ exposure to secondhand smoke and its accompanying health hazards. This is good for individuals, communities and entire economies. The WHO report cites several cases where smoke-free policy implementation was followed by reductions in hospital admissions for acute heart conditions in Argentina, Denmark and Taiwan. Ultimately, reduced tobacco use means lower health care costs and increased productivity in the workplace. It also helps lower-income families redirect money that would be spent on tobacco products toward necessities such as housing and healthy food.

To make bans work, make them comprehensive

The benefits of bans are only fully realized when smoke-free policies are widespread and do not include exceptions, such as “smoking sections” in restaurants. To fully protect people from secondhand smoke, bans should cover all public indoor spaces in all jurisdictions.

Policymakers must resist tobacco industry interference in such policies, as the industry invariably attempts to influence health policies for its own commercial benefit. This includes creating exceptions for heated tobacco products, which tobacco companies claim are “smoke-free”—though this claim remains contested.

Smoke-free spaces lead to less exposure to secondhand smoke, reduced tobacco use, healthier people and healthier economies. Governments should act now to implement smoke-free policies.

*See Annex 2 of the report to learn where smoking is banned by country.